Max Clifford

Max Clifford | |

|---|---|

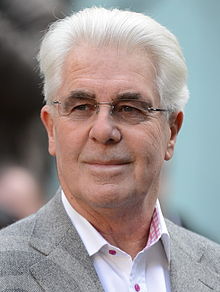

Clifford in 2014 | |

| Born | Maxwell Frank Clifford 6 April 1943 Kingston upon Thames, England |

| Died | 10 December 2017 (aged 74) Huntingdon, England |

| Years active | 1970–2012 |

| Spouses | Elizabeth Porter

(m. 1967; died 2003)Jo Westwood

(m. 2010; div. 2014) |

| Children | 1 |

Maxwell Frank Clifford (6 April 1943 – 10 December 2017) was an English publicist who was particularly associated with promoting "kiss and tell" stories in tabloid newspapers.

In December 2012, as part of Operation Yewtree, Clifford was arrested on suspicion of sexual offences. He was sentenced to eight years in prison in May 2014 after being found guilty of eight counts of indecent assault on four girls and women aged between 15 and 19.[1][2][3][4] He died in December 2017 after suffering a heart attack in HM Prison Littlehey.[5]

Early life

[edit]Maxwell Frank Clifford was born in Kingston upon Thames[6] on 6 April 1943,[6][7] the son of Lilian (née Boffee) and electrician Frank Clifford.[7][8] He was the youngest of four children,[9] with one sister and two brothers.[6]: 16–17 The family survived their father's regular bouts of unemployment, gambling, and alcoholism with the help and support of their grandmother and Clifford's sister, who was employed as a PA to the London Vice-President of Morgan Guarantee Trust Bank.[6] Clifford left school at 15 with no qualifications,[10] and he was sacked within four months of his first job at Ely's department store in Wimbledon. His brother Bernard used his print union connections to secure Clifford a job as editorial assistant on the Eagle. When the publication moved premises, Clifford decided to take redundancy, buying his first house and finding work with the South London Press to train as a journalist.[6]

Career

[edit]Early work as a publicist

[edit]After working in newspapers for a few years, writing an occasional record/music column and running a disco, Clifford replied to an advertisement and joined as the second member of the EMI press office in 1962,[9] under Chief Press Officer Syd Gillingham. As the youngest and the only trained journalist in a team of four, Clifford claimed he was given the job of promoting the then relatively unknown Beatles,[11] including during their first tour of the United States.[6][page needed]

After Gillingham left EMI, he asked Clifford to join him at Chris Hutchins's PR agency.[6][page needed] Among the artists they represented were Paul and Barry Ryan, who introduced Clifford to their stepfather, impresario Harold Davidson, who handled the UK affairs of Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland.[6][page needed]

In 1970, aged 27, and after Gillingham retired, Clifford left Hutchins and started his own agency, Max Clifford Associates.[6] Based in the offices of Joe Cocker's manager, he started off by representing Sinatra, Cocker, Paul and Barry Ryan, Don Partridge, and Marvin Gaye. He later also represented Muhammad Ali and Marlon Brando.[6] Former LWT Press Officer 1980-84, Rosie Brocklehurst said Clifford attempted to elicit favours from LWT press officers in return for other favourable coverage. He was particularly interested in salacious gossip on LWT Light Entertainment celebrities. In 1989, when she had moved to work for Equity, the actors' union, Brocklehurst received a call from 'a terrified young actress' who had been persuaded to give a particularly career damaging 'kiss and tell' story about an incestuous relationship to Clifford as a means of giving her career a boost. The story was due to run in the News of the World but the young actress said it had been entirely fabricated, and that Clifford and she did not know how to get out of it. Brocklehurst called Clifford and persuaded him to drop the story.[citation needed]

Pamella Bordes

[edit]Clifford was approached by a brothel madame, who had provided one of Clifford's clients with various services, worried about publicity from an investigative reporter from the News of the World. Clifford asked the madame to reveal details of her girls and clients, and found that one prostitute, Pamella Bordes, was simultaneously dating Andrew Neil (then editor of The Sunday Times), Donald Trelford (then editor of The Observer), Conservative minister for sport Colin Moynihan, and billionaire arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi.[12][13][14] Clifford rang News of the World editor Patsy Chapman and drip-fed her the story of Bordes through the investigative reporter she was using on the madam. The story was published in March 1989 under the headline "Call Girl Works in Commons", since it was discovered she had a House of Commons security pass arranged by MPs David Shaw and Henry Bellingham. Clifford claimed Bordes was never his client, and that he earned his fee for "writing" the story, which ultimately served the purpose of saving the madame from any adverse publicity or court case.[6][page needed]

Clients

[edit]Clifford came to public attention after creating the infamous "Freddie Starr ate my hamster" headline in 1986 for The Sun in an effort to draw attention to his client, Freddie Starr.[15] In May 2006 the BBC nominated "Freddie Starr ate my hamster" as one of the most familiar British newspaper headlines over the last century.[16] Clifford later represented various clients, including former Liverpool left-wing politician Derek Hatton, for whom Clifford created an affair to change his image;[6][page needed] O. J. Simpson,[15] for which reason Clifford claimed to have received death threats[6][page needed]; Gillian McKeith, whose adverts he believed harmed her image;[17] Rebecca Loos, when she negotiated with the press about her alleged affair with England football captain David Beckham;[6][page needed] and Jade Goody, during the reality star's cervical cancer and death.[18] Clifford represented Simon Cowell for over a decade and was credited with shaping his public image; Cowell dropped Clifford following Clifford's 2014 conviction.[19] In 2016, a judge awarded former client Paul Burrell £5,000 damages after Burrell sued Clifford, saying that Clifford forwarded private material in a fax to Rebekah Brooks at News of the World in 2002.[20]

Journalist Louis Theroux followed Clifford in the BBC Two series When Louis Met... in a 2002 episode titled When Louis Met ... Max Clifford. During filming, it appeared that Clifford was trying to set up Theroux during a PR stunt in Sainsbury's. It backfired after Clifford was heard lying on his microphone, unaware it was still on.[21]

Clifford represented a witness in the case against Gary Glitter.[22] In 2005, Clifford paid damages to settle defamation proceedings brought by Neil and Christine Hamilton after he represented Nadine Milroy-Sloane, who was later found to have falsely accused the pair of sexual assault.[23] Also in 2005, he told reporters that he would not represent Michael Jackson after he was found not guilty of child abuse charges, saying: "It would be the hardest job in PR after [representing] Saddam Hussein".[24] Following the Jimmy Savile sexual abuse scandal, but prior to his arrest, Clifford claimed that dozens of "big name stars" contacted him and feared they would become implicated in the scandal; he claimed that in the 1960s and 70s they "never asked for anybody's birth certificate" before having sex.[25]

LGBT clients

[edit]Clifford helped clients who wished to conceal their sexual orientation from the public. He claimed that he was approached twice by major football clubs to help make players present a "straight" image.[26] In an interview with Pink News, reported on 5 August 2009, Clifford said that if a gay or bisexual football player came out, his career would be over:

To my knowledge there is only one top-flight professional gay footballer who came out – Justin Fashanu. He ended up committing suicide. I have been advising a top premiership star who is bisexual. If it came out that he had gay tendencies, his career would be over in two minutes. Should it be? No, but if you go on the terraces and hear the way fans are, and also, that kind of general attitude that goes with football, it's almost like going back to the dark ages.[27]

Clifford said none of his clients had been outed.[6]

In December 2009, he told The Independent on Sunday that he had represented two high-profile Premier League footballers in the past five years whom he advised to stay in the closet because football "remains in the dark ages, steeped in homophobia".[28]

Politics

[edit]Clifford stated that what motivated him was much more than just money; he said he could not stand hypocrisy in public life, reserved a particular disgust for lying politicians, and watched with growing anger what he thought happened to the National Health Service over the past 20 years.[6] For this reason, and because of his working-class background, Clifford was a traditional Labour supporter who worked to bring down the government of John Major because he felt that the NHS was being mismanaged.[6][page needed]

The Major government

[edit]In light of Clifford's view of the deteriorating state of the NHS – having obtained treatment for his daughter, who had been diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis[6][page needed] – and moral differences with members of the John Major government, Clifford worked to expose stories to help the Labour Party to power. Although not instrumental in exposing David Mellor's affair with Antonia de Sancha, Clifford's battle in representing de Sancha against the contrived post-spin story of the "family man Mellor" handled by counter PR Timothy Bell ultimately derailed Major's 'Back to Basics' agenda. Clifford invented the story which claimed Mellor made love in a Chelsea F.C. football kit, though he was blocked from mentioning it in his memoirs.[29] Clifford also helped to expose Jeffrey Archer's perjury in the 1980s during his candidacy for the post of Mayor of London.[6][page needed]

On 18 February 1995 he was interviewed at length by Andrew Neil for his one-on-one interview show Is This Your Life?, made by Open Media for Channel 4.[30]

The Blair government

[edit]Although a supporter of the Labour Party, Clifford's approach in dealing with the Blair government was similar to that which he employed with Major's preceding Conservative government. The first instance of this was the story of the Secretary of State for Wales, Ron Davies.[6] Clifford was subsequently accused by David Blunkett, at the beginning of November 2005, of having a role in Blunkett's second resignation. This derived from claims made on behalf of a much younger woman, who had become involved with Blunkett, over Blunkett's business interests, which were published in The Times.[6][page needed] Later that week, Clifford was accused of arranging a distraction from the assault made by his friend Rebekah Wade on her then husband, EastEnders actor Ross Kemp, via the "coincidence" of the other "Mitchell brother", Steve McFadden being in a similar incident with an ex-partner. Clifford denied all responsibility.[6]

On 26 April 2006, Clifford represented John Prescott's diary secretary Tracey Temple, in selling her story for "an awful lot more" than £100,000 to the Mail on Sunday. The story was about the affair between Prescott and Temple which took place between 2002 and 2004.[31]

On 4 May 2006, Clifford announced his intention to expose politicians who fail to abide by the standards expected of them in public office. He called his team of undercover investigators "a dedicated and loyal bunch".[6][page needed]

Although he usually backed Labour, Clifford supported, and did some publicity work for, UKIP during the 2004 European election campaign.[32] Clifford said at the time that "The UK Independence Party and myself are in complete agreement that the British people should be the masters of their own destiny through our parliament at Westminster, not subservient to Brussels."[32]

Charity works

[edit]According to his memoirs he handled the publicity for the Daniels family and helped set up the Rhys Daniels Trust from resultant media fees to combat Batten disease.[6][page needed] Clifford was also a patron of the Royal Marsden; however, after his conviction, staff at the hospital stated he was no longer a patron.[33] Also, following his 2014 conviction for indecent assault, Shooting Star CHASE and Woking and Sam Beare Hospices announced that Clifford was no longer a patron for either charity.[19]

Indecent assault convictions

[edit]

Clifford was arrested at his home on 6 December 2012 by Metropolitan Police officers on suspicion of sexual offences; the arrest was part of Operation Yewtree which was set up in the wake of the Jimmy Savile sexual abuse scandal.[34][35] He was taken to a central London police station for questioning.[36][37] The two alleged offences dated from 1977.[38]

On 26 April 2013, he was charged with a further eleven indecent assaults between 1966 and 1985 on girls and women aged 14 to 19.[39] Clifford claimed the allegations were "completely false".[40]

On 28 May 2013, Clifford pleaded not guilty at Westminster Magistrates' Court; a hearing took place at Southwark Crown Court on 12 June 2013 when a date for his trial was set for 4 March 2014.[41][42][43]

On 28 April 2014, Clifford was convicted of eight counts of indecent assault against four victims by a jury at Southwark Crown Court. He was acquitted of two charges of indecent assault, and the jury failed to reach a verdict on another charge.[1][44] Following the verdict the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children's Director of National Services Peter Watt stated:

Max Clifford has rightly been unmasked as a ruthless and manipulative sex offender who preyed for decades on children and young women.[45]

On 2 May 2014, Judge Anthony Leonard sentenced Clifford to a total of eight years in prison.[46] Judge Leonard told Clifford he should serve at least half his sentence in prison,[47] adding that he was sure Clifford had also assaulted a 12-year-old girl in Spain, although this charge could not be pursued in the British courts.[47]

The judge added that if the offences had taken place after the law was changed in 2003, several of the offences of which Clifford was found guilty would have been tried as rape, which carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.[46] One of Clifford's victims explained to the court that Clifford's assault on her (at age 15) had prevented her from having her first sexual relationship with a partner her own age, while another said that in the years following the assault she had cried whenever she saw Clifford on television, and had feared that the police would laugh at her. Clifford dismissed his victims as "fantasists" and "opportunists".[48] The judge concluded that Clifford had caused an "additional element of trauma" to his victims by his "contemptuous attitude" during the trial.[49]

On 7 November 2014, Clifford's appeal against his eight-year sentence for sex offences was rejected by the Court of Appeal.[50] The court ruled the sentence handed to Clifford earlier that year was "justified and correct."[51] The court compared Clifford's case with that of broadcaster Stuart Hall in 2013; Clifford had clowned and claimed innocence, but did not directly dispute the claims of his victims. In contrast Hall had publicly denounced his victims and accused one of seeking "instant notoriety". A lawyer commented on the Clifford appeal court ruling "Nothing Clifford did resembled the disastrous approach taken by Stuart Hall who, prior to pleading guilty to abusing them as girls, denounced his accusers as gold-diggers and liars." Clifford's actions were deemed merely to show no remorse, and not to justify an increased penalty on appeal, although ruling out a reduction in sentence due to mitigating factors; in contrast Hall's sentence was actually increased on appeal.[52][53]

It was reported on 12 March 2015 that Clifford had been arrested again by Operation Yewtree police.[54] On 3 July 2015, Clifford was charged with a single count of indecent assault stemming from an alleged incident from 1981.[55] He pleaded not guilty on 20 October,[56] and was cleared by a jury of the charge on 7 July 2016.[57]

Before his death, Clifford had won the right to challenge his conviction at the Court of Appeal and his daughter, Louise, continued to challenge his 2014 conviction afterwards posthumously. Clifford's conviction was ultimately upheld on 2 April 2019 and the Court of Appeal comprehensively rejected his appeal on all grounds. Lady Justice Rafferty said: "Nothing we heard came anywhere near imperilling the safety of this conviction".[58][59]

Personal life

[edit]Clifford married Elizabeth Louise Porter at St Barnabas Church in Southfields, London, on 3 June 1967. Porter died of lung cancer in Sutton, on 8 April 2003.[60][6] the couple had one daughter, Louise (1971–2023).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Clifford ran and took part in weekly adult parties for his friends and clients around London.[61] This brought him into contact with various madams and prostitutes, a connection which he later used to satisfy the needs of his clients, and introduced him to deviant[tone] behaviour.[6][page needed]

Part of the evidence for his trial of various indecent assaults revolved around the size of his penis, with victims describing it as both a micropenis, and enormous. A doctor measured Clifford's penis at five and a quarter inches long when flaccid, and this fact was used in an attempt to discredit the victims' evidence as unreliable.[62]

In March 2010, the News of the World settled out of court after Clifford sought legal action against it for intercepting his voicemail. After a lunch with editor Rebekah Brooks, the paper agreed to pay Clifford's legal fees and an undisclosed "personal payment" not described as damages. The sum exceeded £1 million. The money was paid in exchange for him exclusively giving the paper stories over the next several years.[63][64]

Clifford lived in Hersham, Surrey, before his incarceration.[65] On 4 April 2010, he married his former PA, Jo Westwood; wedding guests included Des O'Connor, Bobby Davro, and Theo Paphitis.[60] In May 2014, Westwood was granted a decree nisi, subsequently ending her four-year marriage to Clifford.[66]

On 18 August 2014, Clifford was allowed out of HM Prison Littlehey, handcuffed to a prison officer, to attend his brother Bernard's funeral at the North East Surrey Crematorium in South West London.[67] This was also to be his last public appearance, three years before his death on 10 December 2017.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]On 7 December 2017, Clifford collapsed in HM Prison Littlehey after trying to clean his cell. He was taken to Hinchingbrooke Hospital, near Huntingdon, where he died of a heart attack three days later, on 10 December, at the age of 74.[5][68][69]

The inquest into Clifford's death heard medical evidence of his poor health leading up to his death. On 18 December 2019, the coroner ruled that he had died of natural causes.[68][70]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Richard Lister (28 April 2014). "Max Clifford guilty of eight indecent assaults". BBC News Online. BBC. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ "R v Max Clifford". Crimeline. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Max Clifford jailed for eight years". BBC News Online. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Saul, Heather (7 November 2014). "Max Clifford loses appeal over eight-year jail sentence for sex offences". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Jailed Max Clifford dies, aged 74". BBC News Online. 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Levin, Angela; Clifford, Max (2005). Max Clifford: Read All about it. Virgin Books. ISBN 9781852272371.

- ^ a b Barratt, Nick (27 October 2007). "Family Detective – Max Clifford". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Anon (2017) "Clifford, Maxwell". Who's Who (online Oxford University Press ed.). Oxford: A & C Black. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.42631. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Barton, Laura (28 April 2008). "'Life has changed – it's nastier now'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ "Profile: Max Clifford". BBC News. 6 March 2014.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (10 December 2017). "Max Clifford obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Summerskill, Bill (28 July 2002). "Paper tiger". The Observer (London). Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ Roy, Amit (9 October 2005). "A trip down memory lane" Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph (Calcutta). Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Billionaire arms dealer breaks his silence over claims he hired Heather Mills as escort". London Evening Standard. 11 November 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Profile: Max Clifford". BBC. 23 March 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "video about the hamster headline". BBC News. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Owen (14 February 2007). "TV dietician to stop using title Dr in adverts". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (23 March 2009). "Jade Goody, British Reality Television Star, Dies at 27". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b Selby, Jenn (29 April 2014). "Max Clifford guilty: Simon Cowell becomes first high profile client to disassociate himself from publicist after he is 'horrified' at sexual assault verdict". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Paul Burrell wins privacy case damages from disgraced Max Clifford". The Daily Telegraph. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Day, Julia (22 March 2002). "Theroux meets his match in Clifford". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Cash for court 'confessions'". BBC News. 12 November 1999. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Day, Julia (2 February 2005). "Clifford pays out over Hamiltons slur". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "US fans shun Michael Jackson CD". BBC News. 30 July 2005. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Max Clifford: Stars "frightened" over Savile scandal". ITV. 27 October 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Why are there no openly gay footballers?". BBC News. 11 November 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Tippetts, Adrian (5 August 2009). "Exclusive – PR guru Max Clifford: 'If a gay footballer comes out, his career is over'". Pink News. London. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Harris, Nick (20 December 2009). "Two top gay footballers stay in closet". The Independent on Sunday. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ Guy Adams "Pandora: 'Sun' shines on Chelsea fan Mellor", The Independent, 26 April 2006, as reproduced on the Find Articles website. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ Listing on IMDb

- ^ "Prescott angry at lover's claims". BBC News. 30 April 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Clifford joins UKIP election bid". news.bbc.co.uk. 16 January 2004. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (29 April 2014). "Celebrities cut ties with Max Clifford". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ brian may (2 May 2014). "Max Clifford guilty: King of spin expected to close his PR company offices Max Clifford Associates following sentencing today". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Moss, Stephen; Soldal, Hildegunn (21 February 2009). "I could probably help you become the next Paxman". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Max Clifford arrested in sex offences investigation". BBC News. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ O'Carroll, Lisa (6 December 2012). "Max Clifford arrested on suspicion of sexual offences". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Burns, John F. (6 December 2012). "Star Publicist in Britain Is Questioned in Sex Case". The New York Times.

- ^ "Max Clifford charged with 11 indecent assaults". Crown Prosecution Service blog. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ "Max Clifford: PR guru vows to clear name after charges". BBC News. 27 April 2013.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (28 May 2013). "Max Clifford pleads not guilty to 11 indecent assault charges". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "PR consultant Max Clifford denies sex charges". BBC News. 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Max Clifford trial date set for March 2014". BBC News. 12 June 2013.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (28 April 2014). "Max Clifford found guilty of indecently assaulting teenage girls". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Barrett, David (29 April 2014). "Max Clifford trial: public relations guru guilty of eight counts of indecent assault". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Southwark Crown Court – Regina v Maxwell Clifford – Sentencing remarks" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Max Clifford jailed for eight years for sex assaults". London: BBC News. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Max Clifford victims describe impact of abuse". BBC News. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Max Clifford: New Claims Under Police Review". Sky News. 3 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "R -v- Frank Maxwell Clifford". Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Max Clifford loses appeal over sexual assaults conviction". The Guardian. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Rozenberg, Joshua (12 November 2014). "Appeal court ruling on Max Clifford shows how far defendants can go". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Rawlinson, Kevin (10 December 2014). "Max Clifford, jailed former publicist, dies aged 74". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Max Clifford: New Claims Under Police Review". BBC News. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Max Clifford faces indecent assault charge". BBC News. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Max Clifford denies indecently assaulting teenager". BBC News. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "PR guru Max Clifford cleared of sexually assaulting teenage girl in his office". The Daily Telegraph. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ "Max Clifford: Convictions upheld against late publicist". BBC News. 2 April 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Waterson, Jim (2 April 2019). "Max Clifford's conviction for sex offences upheld". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b Rollo, Sarah (4 April 2010). "Max Clifford weds in low-key ceremony". BBC News Online. Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Cadwalladr, Carole (23 July 2006). "Circus Maximus". Observer Magazine. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ Press Association (26 Mar 2014). ". The Guardian.

- ^ Van Natta, Don Jr; Becker, Jo; Bowley, Graham (1 September 2010). "Tabloid Hack Attack on Royals, and Beyond". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Evans, Rob (3 February 2010). "News of the World loses battle over secret phone hacking evidence". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Barrett, David (28 April 2014). "Max Clifford trial: public relations guru guilty of eight counts of indecent assault". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Dixon, Hayley (20 May 2014). "Max Clifford's divorce reveals his marriage was over before his arrest". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ https://www.itv.com/news/london/update/2014-08-18/max-clifford-allowed-out-of-prison-for-his-brothers-funeral/

- ^ a b Lamy, Joel. "Max Clifford received 'slow progress' in treatment before dying at Hinchingbrooke Hospital daughter tells inquest". Peterborough Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Marshall, Francesca (10 December 2017). "Max Clifford dies after collapsing in prison: PR guru was denied medical treatment, family claim". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Max Clifford inquest: Publicist died of natural causes". BBC News. 18 December 2019.

External links

[edit]- Official website at the Wayback Machine (archived 25 February 2014)

- Max Clifford collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Max Clifford: Behind the headlines, BBC News, 11 August 2001

- "Southwark Crown Court – Regina v Maxwell Clifford – Sentencing remarks" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2014.

- Max Clifford at IMDb

- 1943 births

- 2017 deaths

- 20th-century English criminals

- 21st-century English criminals

- English male criminals

- English people convicted of indecent assault

- Charity fundraisers (people)

- Criminals from London

- English male journalists

- English people convicted of child sexual abuse

- English people who died in prison custody

- English prisoners and detainees

- English public relations people

- Labour Party (UK) people

- Operation Yewtree

- People from Hersham

- People from Kingston upon Thames

- Prisoners who died in England and Wales detention

- Violence against women in England

- English republicans