Corporate finance

| Part of a series on financial services |

| Banking |

|---|

|

Corporate finance is the area of finance that deals with the sources of funding, and the capital structure of businesses, the actions that managers take to increase the value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and analysis used to allocate financial resources. The primary goal of corporate finance is to maximize or increase shareholder value.[1]

Correspondingly, corporate finance comprises two main sub-disciplines. [citation needed] Capital budgeting is concerned with the setting of criteria about which value-adding projects should receive investment funding, and whether to finance that investment with equity or debt capital. Working capital management is the management of the company's monetary funds that deal with the short-term operating balance of current assets and current liabilities; the focus here is on managing cash, inventories, and short-term borrowing and lending (such as the terms on credit extended to customers).

The terms corporate finance and corporate financier are also associated with investment banking. The typical role of an investment bank is to evaluate the company's financial needs and raise the appropriate type of capital that best fits those needs. Thus, the terms "corporate finance" and "corporate financier" may be associated with transactions in which capital is raised in order to create, develop, grow or acquire businesses.

Although it is in principle different from managerial finance which studies the financial management of all firms, rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms. Financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession. However, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, while financial management is concerned with the deployment of capital resources to increase a firm's value to the shareholders.

People usually use the word "corporate finance" to talk about deals where existing capital is used and new capital is raised to start up, grow, and support new businesses and projects.[2]

History

[edit]Corporate finance for the pre-industrial world began to emerge in the Italian city-states and the low countries of Europe from the 15th century.

The Dutch East India Company (also known by the abbreviation "VOC" in Dutch) was the first publicly listed company ever to pay regular dividends.[3][4][5] The VOC was also the first recorded joint-stock company to get a fixed capital stock. Public markets for investment securities developed in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century.[6][7][8]

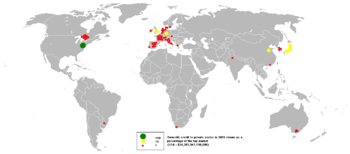

By the early 1800s, London acted as a center of corporate finance for companies around the world, which innovated new forms of lending and investment; see City of London § Economy. The twentieth century brought the rise of managerial capitalism and common stock finance, with share capital raised through listings, in preference to other sources of capital.

Modern corporate finance, alongside investment management, developed in the second half of the 20th century, particularly driven by innovations in theory and practice in the United States and Britain.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Here, see the later sections of History of banking in the United States and of History of private equity and venture capital.

Outline

[edit]The three main questions that corporate finance addresses are: what long-term investments should we make? What methods should we employ to finance the investment? How do we manage our day-to-day financial activities? These three questions bring us to the primary areas of concern in corporate finance: capital budgeting, capital structure, and working capital management.[15][16]

The primary goal of financial management is to maximize or to continually increase shareholder value.[17] [a] This requires that managers find an appropriate balance between: investments in "projects" that increase the firm's long term profitability; and paying excess cash in the form of dividends to shareholders; also considered will be paying back creditor related debt.[17][21]

Choosing between investment projects will thus be based upon several inter-related criteria. [1] (1) Corporate management seeks to maximize the value of the firm by investing in projects which yield a positive net present value when valued using an appropriate discount rate in consideration of risk. (2) These projects must also be financed appropriately. (3) If no growth is possible by the company and excess cash surplus is not needed to the firm, then financial theory suggests that management should return some or all of the excess cash to shareholders (i.e., distribution via dividends).[22]

The first two criteria concern "capital budgeting", the planning of value-adding, long-term corporate financial projects relating to investments funded through and affecting the firm's capital structure, and where management must allocate the firm's limited resources between competing opportunities ("projects"). [23] Capital budgeting is thus also concerned with the setting of criteria about which projects should receive investment funding to increase the value of the firm, and whether to finance that investment with equity or debt capital.[24] Investments should be made on the basis of value-added to the future of the corporation. Projects that increase a firm's value may include a wide variety of different types of investments, including but not limited to, expansion policies, or mergers and acquisitions.

The third criterion relates to dividend policy. In general, managers of growth companies (i.e. firms that earn high rates of return on invested capital) will use most of the firm's capital resources and surplus cash on investments and projects so the company can continue to expand its business operations into the future. When companies reach maturity levels within their industry (i.e. companies that earn approximately average or lower returns on invested capital), managers of these companies will use surplus cash to payout dividends to shareholders. Thus, when no growth or expansion is likely, and excess cash surplus exists and is not needed, then management is expected to pay out some or all of those surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends or to repurchase the company's stock through a share buyback program.[25][26]

Capital structure

[edit]Achieving the goals of corporate finance requires that any corporate investment be financed appropriately.[27] The sources of financing are, generically, capital self-generated by the firm and capital from external funders, obtained by issuing new debt and equity (and hybrid- or convertible securities). However, as above, since both hurdle rate and cash flows (and hence the riskiness of the firm) will be affected, the financing mix will impact the valuation of the firm, and a considered decision [28] is required here. See Balance sheet, WACC. Finally, there is much theoretical discussion as to other considerations that management might weigh here.

Sources of capital

[edit]Debt capital

[edit]Corporations may rely on borrowed funds (debt capital or credit) as sources of investment to sustain ongoing business operations or to fund future growth. Debt comes in several forms, such as through bank loans, notes payable, or bonds issued to the public. Bonds require the corporation to make regular interest payments (interest expenses) on the borrowed capital until the debt reaches its maturity date, therein the firm must pay back the obligation in full. One exception is zero-coupon bonds (or "zeros"). Debt payments can also be made in the form of sinking fund provisions, whereby the corporation pays annual installments of the borrowed debt above regular interest charges. Corporations that issue callable bonds are entitled to pay back the obligation in full whenever the company feels it is in their best interest to pay off the debt payments. If interest expenses cannot be made by the corporation through cash payments, the firm may also use collateral assets as a form of repaying their debt obligations (or through the process of liquidation).

Equity capital

[edit]Corporations can alternatively sell shares of the company to investors to raise capital. Investors, or shareholders, expect that there will be an upward trend in value of the company (or appreciate in value) over time to make their investment a profitable purchase. Shareholder value is increased when corporations invest equity capital and other funds into projects (or investments) that earn a positive rate of return for the owners. Investors prefer to buy shares of stock in companies that will consistently earn a positive rate of return on capital in the future, thus increasing the market value of the stock of that corporation. Shareholder value may also be increased when corporations payout excess cash surplus (funds from retained earnings that are not needed for business) in the form of dividends.

Preferred stock

[edit]Preferred stock is a specialized form of financing which combines properties of common stock and debt instruments, and is generally considered a hybrid security. Preferreds are senior (i.e. higher ranking) to common stock, but subordinate to bonds in terms of claim (or rights to their share of the assets of the company).[29]

Preferred stock usually carries no voting rights,[30] but may carry a dividend and may have priority over common stock in the payment of dividends and upon liquidation. Terms of the preferred stock are stated in a "Certificate of Designation".

Similar to bonds, preferred stocks are rated by the major credit-rating companies. The rating for preferreds is generally lower, since preferred dividends do not carry the same guarantees as interest payments from bonds and they are junior to all creditors.[31]

Preferred stock is a special class of shares which may have any combination of features not possessed by common stock. The following features are usually associated with preferred stock:[32]

- Preference in dividends

- Preference in assets, in the event of liquidation

- Convertibility to common stock.

- Callability, at the option of the corporation

- Nonvoting

Capitalization structure

[edit]

As outlined, the financing "mix" will impact the valuation (as well as the cashflows) of the firm, and must therefore be structured appropriately: there are then two interrelated considerations [28] here:

- Management must identify the "optimal mix" of financing – the capital structure that results in maximum firm value [33] - but must also take other factors into account (see trade-off theory below). Financing a project through debt results in a liability or obligation that must be serviced, thus entailing cash flow implications independent of the project's degree of success. Equity financing is less risky with respect to cash flow commitments, but results in a dilution of share ownership, control and earnings. The cost of equity (see CAPM and APT) is also typically higher than the cost of debt - which is, additionally, a deductible expense – and so equity financing may result in an increased hurdle rate which may offset any reduction in cash flow risk.[34][35]

- Management must attempt to match the long-term financing mix to the assets being financed as closely as possible, in terms of both timing and cash flows. Managing any potential asset liability mismatch or duration gap entails matching the assets and liabilities respectively according to maturity pattern ("cashflow matching") or duration ("immunization"); managing this relationship in the short-term is a major function of working capital management, as discussed below. Other techniques, such as securitization, or hedging using interest rate- or credit derivatives, are also common. See: Asset liability management; Treasury management; Credit risk; Interest rate risk.

Related considerations

[edit]Much of the theory here, falls under the umbrella of the Trade-Off Theory in which firms are assumed to trade-off the tax benefits of debt with the bankruptcy costs of debt when choosing how to allocate the company's resources. However economists have developed a set of alternative theories about how managers allocate a corporation's finances.

One of the main alternative theories of how firms manage their capital funds is the Pecking Order Theory (Stewart Myers), which suggests that firms avoid external financing while they have internal financing available and avoid new equity financing while they can engage in new debt financing at reasonably low interest rates.

Also, the capital structure substitution theory hypothesizes that management manipulates the capital structure such that earnings per share (EPS) are maximized. An emerging area in finance theory is right-financing whereby investment banks and corporations can enhance investment return and company value over time by determining the right investment objectives, policy framework, institutional structure, source of financing (debt or equity) and expenditure framework within a given economy and under given market conditions.

One of the more recent innovations in this area from a theoretical point of view is the market timing hypothesis. This hypothesis, inspired by the behavioral finance literature, states that firms look for the cheaper type of financing regardless of their current levels of internal resources, debt and equity.

Capital budgeting

[edit]The process of allocating financial resources to major investment- or capital expenditure is known as capital budgeting. [36] [23] Consistent with the overall goal of increasing firm value, the decisioning here focuses on whether the investment in question is worthy of funding through the firm's capitalization structures (debt, equity or retained earnings as above). To be considered acceptable, the investment must be value additive re: (i) improved operating profit and cash flows; as combined with (ii) any new funding commitments and capital implications. Re the latter: if the investment is large in the context of the firm as a whole, so the discount rate applied by outside investors to the (private) firm's equity may be adjusted upwards to reflect the new level of risk, [37] thus impacting future financing activities and overall valuation. More sophisticated treatments will thus produce accompanying sensitivity- and risk metrics, and will incorporate any inherent contingencies. The focus of capital budgeting is on major "projects" - often investments in other firms, or expansion into new markets or geographies - but may extend also to new plants, new / replacement machinery, new products, and research and development programs; day to day operational expenditure is the realm of financial management as below.

Investment and project valuation

[edit]In general,[38] each "project's" value will be estimated using a discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation, and the opportunity with the highest value, as measured by the resultant net present value (NPV) will be selected (first applied in a corporate finance setting by Joel Dean in 1951). This requires estimating the size and timing of all of the incremental cash flows resulting from the project. Such future cash flows are then discounted to determine their present value (see Time value of money). These present values are then summed, and this sum net of the initial investment outlay is the NPV. See Financial modeling § Accounting for general discussion, and Valuation using discounted cash flows for the mechanics, with discussion re modifications for corporate finance.

The NPV is greatly affected by the discount rate. Thus, identifying the proper discount rate – often termed, the project "hurdle rate"[39] – is critical to choosing appropriate projects and investments for the firm. The hurdle rate is the minimum acceptable return on an investment – i.e., the project appropriate discount rate. The hurdle rate should reflect the riskiness of the investment, typically measured by volatility of cash flows, and must take into account the project-relevant financing mix.[40] Managers use models such as the CAPM or the APT to estimate a discount rate appropriate for a particular project, and use the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to reflect the financing mix selected. (A common error in choosing a discount rate for a project is to apply a WACC that applies to the entire firm. Such an approach may not be appropriate where the risk of a particular project differs markedly from that of the firm's existing portfolio of assets.)

In conjunction with NPV, there are several other measures used as (secondary) selection criteria in corporate finance; see Capital budgeting § Ranked projects. These are visible from the DCF and include discounted payback period, IRR, Modified IRR, equivalent annuity, capital efficiency, and ROI. Alternatives (complements) to NPV, which more directly consider economic profit, include residual income valuation, MVA / EVA (Joel Stern, Stern Stewart & Co) and APV (Stewart Myers). With the cost of capital correctly and correspondingly adjusted, these valuations should yield the same result as the DCF. See also list of valuation topics.

Sensitivity and scenario analysis

[edit]Given the uncertainty inherent in project forecasting and valuation, [41] [42] [43] analysts will wish to assess the sensitivity of project NPV to the various inputs (i.e. assumptions) to the DCF model. In a typical sensitivity analysis the analyst will vary one key factor while holding all other inputs constant, ceteris paribus. The sensitivity of NPV to a change in that factor is then observed, and is calculated as a "slope": ΔNPV / Δfactor. For example, the analyst will determine NPV at various growth rates in annual revenue as specified (usually at set increments, e.g. -10%, -5%, 0%, 5%...), and then determine the sensitivity using this formula. Often, several variables may be of interest, and their various combinations produce a "value-surface"[44] (or even a "value-space"), where NPV is then a function of several variables. See also Stress testing.

Using a related technique, analysts also run scenario based forecasts of NPV. Here, a scenario comprises a particular outcome for economy-wide, "global" factors (demand for the product, exchange rates, commodity prices, etc.) as well as for company-specific factors (unit costs, etc.). As an example, the analyst may specify various revenue growth scenarios (e.g. -5% for "Worst Case", +5% for "Likely Case" and +15% for "Best Case"), where all key inputs are adjusted so as to be consistent with the growth assumptions, and calculate the NPV for each. Note that for scenario based analysis, the various combinations of inputs must be internally consistent (see discussion at Financial modeling), whereas for the sensitivity approach these need not be so. An application of this methodology is to determine an "unbiased" NPV, where management determines a (subjective) probability for each scenario – the NPV for the project is then the probability-weighted average of the various scenarios; see First Chicago Method. (See also rNPV, where cash flows, as opposed to scenarios, are probability-weighted.)

Quantifying uncertainty

[edit]A further advancement which "overcomes the limitations of sensitivity and scenario analyses by examining the effects of all possible combinations of variables and their realizations"[45] is to construct stochastic[46] or probabilistic financial models – as opposed to the traditional static and deterministic models as above.[42] For this purpose, the most common method is to use Monte Carlo simulation to analyze the project's NPV. This method was introduced to finance by David B. Hertz in 1964, although it has only recently become common: today analysts are even able to run simulations in spreadsheet based DCF models, typically using a risk-analysis add-in, such as @Risk or Crystal Ball. Here, the cash flow components that are (heavily) impacted by uncertainty are simulated, mathematically reflecting their "random characteristics". In contrast to the scenario approach above, the simulation produces several thousand random but possible outcomes, or trials, "covering all conceivable real world contingencies in proportion to their likelihood;"[47] see Monte Carlo Simulation versus "What If" Scenarios. The output is then a histogram of project NPV, and the average NPV of the potential investment – as well as its volatility and other sensitivities – is then observed. This histogram provides information not visible from the static DCF: for example, it allows for an estimate of the probability that a project has a net present value greater than zero (or any other value).

Continuing the above example: instead of assigning three discrete values to revenue growth, and to the other relevant variables, the analyst would assign an appropriate probability distribution to each variable (commonly triangular or beta), and, where possible, specify the observed or supposed correlation between the variables. These distributions would then be "sampled" repeatedly – incorporating this correlation – so as to generate several thousand random but possible scenarios, with corresponding valuations, which are then used to generate the NPV histogram. The resultant statistics (average NPV and standard deviation of NPV) will be a more accurate mirror of the project's "randomness" than the variance observed under the scenario based approach. (These are often used as estimates of the underlying "spot price" and volatility for the real option valuation below; see Real options valuation § Valuation inputs.) A more robust Monte Carlo model would include the possible occurrence of risk events - e.g., a credit crunch - that drive variations in one or more of the DCF model inputs.

Valuing flexibility

[edit]In many cases, for example R&D projects, a project may open (or close) various paths of action to the company, but this reality will not (typically) be captured in a strict NPV approach.[48] Some analysts account for this uncertainty by adjusting the discount rate (e.g. by increasing the cost of capital) or the cash flows (using certainty equivalents, or applying (subjective) "haircuts" to the forecast numbers; see Penalized present value).[49][50] Even when employed, however, these latter methods do not normally properly account for changes in risk over the project's lifecycle and hence fail to appropriately adapt the risk adjustment.[51][52] Management will therefore (sometimes) employ tools which place an explicit value on these options. So, whereas in a DCF valuation the most likely or average or scenario specific cash flows are discounted, here the "flexible and staged nature" of the investment is modelled, and hence "all" potential payoffs are considered. See further under Real options valuation. The difference between the two valuations is the "value of flexibility" inherent in the project.

The two most common tools are Decision Tree Analysis (DTA)[41] and real options valuation (ROV);[53] they may often be used interchangeably:

- DTA values flexibility by incorporating possible events (or states) and consequent management decisions. (For example, a company would build a factory given that demand for its product exceeded a certain level during the pilot-phase, and outsource production otherwise. In turn, given further demand, it would similarly expand the factory, and maintain it otherwise. In a DCF model, by contrast, there is no "branching" – each scenario must be modelled separately.) In the decision tree, each management decision in response to an "event" generates a "branch" or "path" which the company could follow; the probabilities of each event are determined or specified by management. Once the tree is constructed: (1) "all" possible events and their resultant paths are visible to management; (2) given this "knowledge" of the events that could follow, and assuming rational decision making, management chooses the branches (i.e. actions) corresponding to the highest value path probability weighted; (3) this path is then taken as representative of project value. See Decision theory § Choice under uncertainty.

- ROV is usually used when the value of a project is contingent on the value of some other asset or underlying variable. (For example, the viability of a mining project is contingent on the price of gold; if the price is too low, management will abandon the mining rights, if sufficiently high, management will develop the ore body. Again, a DCF valuation would capture only one of these outcomes.) Here: (1) using financial option theory as a framework, the decision to be taken is identified as corresponding to either a call option or a put option; (2) an appropriate valuation technique is then employed – usually a variant on the binomial options model or a bespoke simulation model, while Black–Scholes type formulae are used less often; see Contingent claim valuation. (3) The "true" value of the project is then the NPV of the "most likely" scenario plus the option value. (Real options in corporate finance were first discussed by Stewart Myers in 1977; viewing corporate strategy as a series of options was originally per Timothy Luehrman, in the late 1990s.) See also § Option pricing approaches under Business valuation.

Dividend policy

[edit]Dividend policy is concerned with financial policies regarding the payment of a cash dividend in the present or retaining earnings and then paying an increased dividend at a later stage. The policy will be set based upon the type of company and what management determines is the best use of those dividend resources for the firm and its shareholders. Practical and theoretical considerations - interacting with the above funding and investment decisioning, and re overall firm value - will inform this thinking. [54] [55]

Considerations

[edit]In general, whether [56] to issue dividends,[54] and what amount, is determined on the basis of the company's unappropriated profit (excess cash) and influenced by the company's long-term earning power. In all instances, as above, the appropriate dividend policy is in parallel directed by that which maximizes long-term shareholder value.

When cash surplus exists and is not needed by the firm, then management is expected to pay out some or all of those surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends or to repurchase the company's stock through a share buyback program. Thus, if there are no NPV positive opportunities, i.e. projects where returns exceed the hurdle rate, and excess cash surplus is not needed, then management should return (some or all of) the excess cash to shareholders as dividends.

This is the general case, however the "style" of the stock may also impact the decision. Shareholders of a "growth stock", for example, expect that the company will retain (most of) the excess cash surplus so as to fund future projects internally to help increase the value of the firm. Shareholders of value- or secondary stocks, on the other hand, would prefer management to pay surplus earnings in the form of cash dividends, especially when a positive return cannot be earned through the reinvestment of undistributed earnings; a share buyback program may be accepted when the value of the stock is greater than the returns to be realized from the reinvestment of undistributed profits.

Management will also choose the form of the dividend distribution, as stated, generally as cash dividends or via a share buyback. Various factors may be taken into consideration: where shareholders must pay tax on dividends, firms may elect to retain earnings or to perform a stock buyback, in both cases increasing the value of shares outstanding. Alternatively, some companies will pay "dividends" from stock rather than in cash or via a share buyback as mentioned; see Corporate action.

Dividend theory

[edit]There are several schools of thought on dividends, in particular re their impact on firm value. [54] A key consideration will be whether there are any tax disadvantages associated with dividends: i.e. dividends attract a higher tax rate as compared, e.g., to capital gains; see dividend tax and Retained earnings § Tax implications. Here, per the Modigliani–Miller theorem: if there are no such disadvantages - and companies can raise equity finance cheaply, i.e. can issue stock at low cost - then dividend policy is value neutral; if dividends suffer a tax disadvantage, then increasing dividends should reduce firm value. Regardless, but particularly in the second (more realistic) case, other considerations apply.

The first set relates to investor preferences and behavior (see Clientele effect). Investors are seen to prefer a “bird in the hand” - i.e. cash dividends are certain as compared to income from future capital gains - and in fact, commonly employ some form of dividend valuation model in valuing shares. Relatedly, investors will then prefer a stable or "smooth" dividend payout - as far as is reasonable given earnings prospects and sustainability - which will then positively impact share price; see Lintner model. Cash dividends may also allow management to convey (insider) information about corporate performance; and increasing a company's dividend payout may then predict (or lead to) favorable performance of the company's stock in the future; see Dividend signaling hypothesis

The second set relates to management's thinking re capital structure and earnings, overlapping the above. Under a "Residual dividend policy" - i.e. as contrasted with a "smoothed" payout policy - the firm will use retained profits to finance capital investments if cheaper than the same via equity financing; see again Pecking order theory. Similarly, under the Walter model, dividends are paid only if capital retained will earn a higher return than that available to investors (proxied: ROE > Ke). Management may also want to "manipulate" the capital structure - including by paying or not paying dividends - such that earnings per share are maximized; see Capital structure substitution theory.

Working capital management

[edit]Managing the corporation's working capital position so as to sustain ongoing business operations is referred to as working capital management.[57][58] This entails, essentially, managing the relationship between a firm's short-term assets and its short-term liabilities, conscious of various considerations. Here, as above, the goal of Corporate Finance is the maximization of firm value. In the context of long term, capital budgeting, firm value is enhanced through appropriately selecting and funding NPV positive investments. These investments, in turn, have implications in terms of cash flow and cost of capital. The goal of Working Capital (i.e. short term) management is therefore to ensure that the firm is able to operate, and that it has sufficient cash flow to service long-term debt, and to satisfy both maturing short-term debt and upcoming operational expenses. In so doing, firm value is enhanced when, and if, the return on capital exceeds the cost of capital; See Economic value added (EVA). Managing short term finance along with long term finance is therefore one task of a modern CFO.

Working capital

[edit]Working capital is the amount of funds that are necessary for an organization to continue its ongoing business operations, until the firm is reimbursed through payments for the goods or services it has delivered to its customers.[59] Working capital is measured through the difference between resources in cash or readily convertible into cash (Current Assets), and cash requirements (Current Liabilities). As a result, capital resource allocations relating to working capital are always current, i.e. short-term.

In addition to time horizon, working capital management differs from capital budgeting in terms of discounting and profitability considerations; decisions here are also "reversible" to a much larger extent. (Considerations as to risk appetite and return targets remain identical, although some constraints – such as those imposed by loan covenants – may be more relevant here).

The (short term) goals of working capital are therefore not approached on the same basis as (long term) profitability, and working capital management applies different criteria in allocating resources: the main considerations are (1) cash flow / liquidity and (2) profitability / return on capital (of which cash flow is probably the most important).

- The most widely used measure of cash flow is the net operating cycle, or cash conversion cycle. This represents the time difference between cash payment for raw materials and cash collection for sales. The cash conversion cycle indicates the firm's ability to convert its resources into cash. Because this number effectively corresponds to the time that the firm's cash is tied up in operations and unavailable for other activities, management generally aims at a low net count. (Another measure is gross operating cycle which is the same as net operating cycle except that it does not take into account the creditors deferral period.)

- In this context, the most useful measure of profitability is return on capital (ROC). The result is shown as a percentage, determined by dividing relevant income for the 12 months by capital employed; return on equity (ROE) shows this result for the firm's shareholders. As outlined, firm value is enhanced when, and if, the return on capital exceeds the cost of capital.

Management of working capital

[edit]Guided by the above criteria, management will use a combination of policies and techniques for the management of working capital.[60] These policies aim at managing the current assets (generally cash and cash equivalents, inventories and debtors) and the short term financing, such that cash flows and returns are acceptable.[58]

- Cash management. Identify the cash balance which allows for the business to meet day to day expenses, but reduces cash holding costs.

- Inventory management. Identify the level of inventory which allows for uninterrupted production but reduces the investment in raw materials – and minimizes reordering costs – and hence increases cash flow. See discussion under Inventory optimization and Supply chain management. Note that "inventory" is usually the realm of operations management: given the potential impact on cash flow, and on the balance sheet in general, finance typically "gets involved in an oversight or policing way".[61]: 714

- Debtors management. There are two inter-related roles here: (1) Identify the appropriate credit policy, i.e. credit terms which will attract customers, such that any impact on cash flows and the cash conversion cycle will be offset by increased revenue and hence Return on Capital (or vice versa); see Discounts and allowances. (2) Implement appropriate credit scoring policies and techniques such that the risk of default on any new business is acceptable given these criteria.

- Short term financing. Identify the appropriate source of financing, given the cash conversion cycle: the inventory is ideally financed by credit granted by the supplier; however, it may be necessary to utilize a bank loan (or overdraft), or to "convert debtors to cash" through "factoring"; see generally, trade finance.

Other areas

[edit]Investment banking

[edit]As discussed, corporate finance comprises the activities, analytical methods, and techniques that deal with the company's long-term investments, finances and capital. Re the latter, when capital must be raised for the corporation or shareholders, the "corporate finance team" will engage [62] its investment bank. The bank will then facilitate the required share listing (IPO or SEO) or bond issuance, as appropriate given the above anaysis. Thereafter the bank will work closely with the corporate re servicing the new securities, and managing its presence in the capital markets more generally (offering advisory, financial advisory, deal advisory, and / or transaction advisory [63] services).

Use of the term "corporate finance", correspondingly, varies considerably across the world. In the United States, "Corporate Finance" corresponds to the first usage. A professional here may be referred to as a "corporate finance analyst" and will typically be based in the FP&A area, reporting to the CFO. [62] [64] See Financial analyst § Financial planning and analysis. In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries, [63] on the other hand, "corporate finance" and "corporate financier" are associated with investment banking.

Financial risk management

[edit]Financial risk management,[46][65] generally, is focused on measuring and managing market risk, credit risk and operational risk. Within corporates [65] (i.e. as opposed to banks), the scope extends to preserving (and enhancing) the firm's economic value.[66] It will then overlap both corporate finance and enterprise risk management: addressing risks to the firm's overall strategic objectives, by focusing on the financial exposures and opportunities arising from business decisions, and their link to the firm’s appetite for risk, as well as their impact on share price. (In large firms, Risk Management typically exists as an independent function, with the CRO consulted on capital-investment and other strategic decisions.) Re corporate finance, both operational and funding issues are addressed:

- Businesses actively manage any impact on profitability, cash flow, and hence firm value, due to credit and operational factors - this, overlapping "working capital management" to a large extent. Firms then devote much time and effort to forecasting, analytics and performance monitoring. (The above analyst role; see also "ALM" and treasury management.)

- Firm exposure to market (and business) risk is a direct result of previous capital investments and funding decisions: where applicable here,[67][68] typically in large corporates and under guidance from their investment bankers, firms actively manage and hedge these exposures using traded financial instruments, usually standard derivatives, creating interest rate-, commodity- and foreign exchange hedges; see Cash flow hedge.

Corporate governance

[edit]Broadly, corporate governance considers the mechanisms, processes, practices, and relations by which corporations are controlled and operated by their boards of directors, managers, shareholders, and stakeholders. In the context of corporate finance, [69] a more specific concern will be that executives do not "serve their own vested interests" to the detriment of capital providers. [70] There are several considerations:

- As regards investments: acquisitions and takeovers may be driven by management interests (a larger company) rather than stockholder interests; [69] managers may then overpay on investments, [69] reducing firm value.

- Several issues inhere also in the capital structure and management will be expected to balance these: [69] Stockholders, with "potentially unlimited" [70] upside, have an incentive to take riskier projects than bondholders, who earn a fixed return. [71]

- Stockholders will also wish to pay more out in dividends than bondholders would like them to.

In general, here, debt may be seen as "an internal means of controlling management", which has to work hard to ensure that repayments are met, [72] balancing these interests, and also limiting the possibility of overpaying on investments. Granting Executive stock options, alternatively, is seen as a mechanism to align management with stockholder interests. A more formal treatment is offered under agency theory, [73] where these problems and approaches can be seen, and hence analysed, as real options; [74] see Principal–agent problem § Options framework for discussion.

See also

[edit]- Outline of corporate finance

- Financial economics § Certainty

- Financial economics § Corporate finance theory

- Outline of finance § Corporate finance theory

- Capital management

- Corporate budget

- Corporate governance

- Corporate tax

- FP&A

- Financial accounting

- Financial analysis

- Financial management

- Financial planning

- Growth stock

- Investment bank

- Private equity

- Security (finance)

- Stock market

- Strategic financial management

- Venture capital

- Professional certification in financial services § Corporate finance

- Lists:

Notes

[edit]- ^ A long-standing debate in corporate finance has focused on whether maximizing shareholder value or stakeholder value should be the primary focus of corporate managers, with stakeholders widely interpreted to refer to shareholders, employees, suppliers and the local community.[18] In 2019, the Business Roundtable released a statement, signed by 181 prominent U.S. CEOs, which committed to lead their companies for "the benefit of all stakeholders".[19] Despite intense debate and recent momentum for the stakeholder theory, shareholder theory still dominates corporate world strategy.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b See Corporate Finance: First Principles, Aswath Damodaran, New York University's Stern School of Business

- ^ "What is corporate finance?". www.icaew.com. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ Freedman, Roy S.: Introduction to Financial Technology. (Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0123704782)

- ^ DK Publishing (Dorling Kindersley): The Business Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained). (DK Publishing, 2014, ISBN 1465415858)

- ^ Huston, Jeffrey L.: The Declaration of Dependence: Dividends in the Twenty-First Century. (Archway Publishing, 2015, ISBN 1480825042)

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2002). Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, p. 15. "Moreover, their company [the Dutch East India Company] was a permanent joint-stock company, unlike the English company, which did not become permanent until 1650."

- ^ Smith, B. Mark: A History of the Global Stock Market: From Ancient Rome to Silicon Valley. (University of Chicago Press, 2003, ISBN 9780226764047), p. 17. As Mark Smith (2003) notes, "the first joint-stock companies had actually been created in England in the sixteenth century. These early joint-stock firms, however, possessed only temporary charters from the government, in some cases for one voyage only. (One example was the Muscovy Company, chartered in England in 1533 for trade with Russia; another, chartered the same year, was a company with the intriguing title Guinea Adventurers.) The Dutch East India Company was the first joint-stock company to have a permanent charter."

- ^ Clarke, Thomas; Branson, Douglas: The SAGE Handbook of Corporate Governance. (SAGE Publications Ltd., 2012 ISBN 9781412929806), p. 431. "The EIC first issued permanent shares in 1657 (Harris, 2005: 45)."

- ^ Baskin, Jonathan; Baskin, Jonathan Barron; Miranti, Paul J. Jr. (1999-12-28). A History of Corporate Finance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521655361.

- ^ Smith, Clifford W.; Jensen, Michael C. (2000-09-29). "The Theory of Corporate Finance: A Historical Overview". Rochester, NY. SSRN 244161.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cassis, Youssef (2006). Capitals of Capital: A History of International Financial Centres, 1780–2005. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 74–5. ISBN 978-0-511-33522-8.

- ^ Michie, Ranald (2006). The Global Securities Market: A History. OUP Oxford. p. 149. ISBN 0191608599.

- ^ Cameron, Rondo; Bovykin, V.I., eds. (1991). International Banking: 1870–1914. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-506271-7.

- ^ Roberts, Richard (2008). The City: A Guide to London's Global Financial Centre. Economist. pp. 6, 12–13, 88–89. ISBN 9781861978585.

- ^ "Introduction to Corporate Finance" (PDF). Introduction to Corporate Finance - KSU. 2010.

- ^ Alawi, Suha. "Introduction to Corporate Finance". Introduction to Corporate Finance - KAU.

- ^ a b Jim McMenamin (11 September 2002). Financial Management: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-134-67624-8.

- ^ Smith, H. Jeff (2003-07-15). "The Shareholders vs. Stakeholders Debate". MIT Sloan Management Review.

- ^ "Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote 'An Economy That Serves All Americans'". www.businessroundtable.org. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ Chuma, Casius; Qutieshat, Abubaker (2023-03-30). "Where Does the Value of A Corporation Lie? A Literature Review". Economia Aziendale Online. 14 (1): 15–32. doi:10.13132/2038-5498/14.1.15-32. ISSN 2038-5498.

- ^ Carlos Correia; David K. Flynn; Enrico Uliana; Michael Wormald (15 January 2007). Financial Management. Juta and Company Ltd. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-0-7021-7157-4.

- ^ Financial Management; Principles and Practice. Freeload Press, Inc. 1968. pp. 265–. ISBN 978-1-930789-02-9.

- ^ a b See: Campbell R. Harvey (1997). Investment Decisions and Capital Budgeting (Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine); Don M. Chance. (ND). The Investment Decision of the Corporation

- ^ Myers, Stewart C. "Interactions of corporate financing and investment decisions—implications for capital budgeting." The Journal of finance 29.1 (1974): 1-25.

- ^ Pamela P. Peterson; Frank J. Fabozzi (4 February 2004). Capital Budgeting: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-44642-2.

- ^ Lawrence J. Gitman; Michael D. Joehnk; George E. Pinches (1985). Managerial finance. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060423360.

- ^ See: The Financing Decision of the Corporation Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. Don M. Chance; Capital Structure, Prof. Aswath Damodaran

- ^ a b The design of the capital structure, Ch 35. in Vernimmen et. al.

- ^ Drinkard, T., A Primer On Preferred Stocks., Investopedia

- ^ "Preferred Stock ... generally carries no voting rights unless scheduled dividends have been omitted." – Quantum Online Archived 2012-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Drinkard, T.

- ^ Kieso, Donald E.; Weygandt, Jerry J. & Warfield, Terry D. (2007). Intermediate Accounting (12th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-471-74955-4..

- ^ Capital Structure: Implications Archived 2012-01-21 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. John C. Groth, Texas A&M University; A Generalised Procedure for Locating the Optimal Capital Structure, Ruben D. Cohen, Citigroup

- ^ See:Optimal Balance of Financial Instruments: Long-Term Management, Market Volatility & Proposed Changes, Nishant Choudhary, LL.M. 2011 (Business & finance), George Washington University Law School

- ^ Mayer, Colin (1988). "New issues in corporate finance". European Economic Review. 32 (5): 1167–1183. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(88)90077-3.

- ^ Pinkasovitch, Arthur. "An Introduction to Capital Budgeting". Investopedia. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Aswath Damodaran (2022). The cost of capital: misunderstood, misestimated and misused!

- ^ See: Valuation, Prof. Aswath Damodaran; Equity Valuation, Prof. Campbell R. Harvey

- ^ See for example Campbell R. Harvey's Hypertextual Finance Glossary or investopedia.com

- ^ Prof. Aswath Damodaran: Estimating Hurdle Rates

- ^ a b "Capital Budgeting Under Risk". Ch.9 in Schaum's outline of theory and problems of financial management, Jae K. Shim and Joel G. Siegel.

- ^ a b Probabilistic Approaches: Scenario Analysis, Decision Trees and Simulations, Prof. Aswath Damodaran

- ^ The Role of Risk in Capital Budgeting - Scenario and Simulation Assessments, Boundless Finance

- ^ For example, mining companies sometimes employ the "Hill of Value" methodology in their planning; see, e.g., B. E. Hall (2003). "How Mining Companies Improve Share Price by Destroying Shareholder Value" and I. Ballington, E. Bondi, J. Hudson, G. Lane and J. Symanowitz (2004). "A Practical Application of an Economic Optimisation Model in an Underground Mining Environment" Archived 2013-07-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Virginia Clark, Margaret Reed, Jens Stephan (2010). Using Monte Carlo simulation for a capital budgeting project, Management Accounting Quarterly, Fall, 2010

- ^ a b See David Shimko (2009). Quantifying Corporate Financial Risk. archived 2010-07-17.

- ^ The Flaw of Averages Archived 2011-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. Sam Savage, Stanford University.

- ^ See: Real Options Analysis and the Assumptions of the NPV Rule, Tom Arnold & Richard Shockley

- ^ Aswath Damodaran: Risk Adjusted Value; Ch 5 in Strategic Risk Taking: A Framework for Risk Management. Wharton School Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0-13-199048-9

- ^ See: §32 "Certainty Equivalent Approach" & §165 "Risk Adjusted Discount Rate" in: Joel G. Siegel; Jae K. Shim; Stephen Hartman (1 November 1997). Schaum's quick guide to business formulas: 201 decision-making tools for business, finance, and accounting students. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-058031-2. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Michael C. Ehrhardt and John M. Wachowicz, Jr (2006). Capital Budgeting and Initial Cash Outlay (ICO) Uncertainty. Financial Decisions, Summer 2006, Article 2

- ^ Dan Latimore: Calculating value during uncertainty. IBM Institute for Business Value

- ^ See:Identifying real options, Prof. Campbell R. Harvey; Applications of option pricing theory to equity valuation, Prof. Aswath Damodaran; How Do You Assess The Value of A Company's "Real Options"? Archived 2019-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, Prof. Alfred Rappaport Columbia University & Michael Mauboussin

- ^ a b c See Dividend Policy, Prof. Aswath Damodaran

- ^ James Chet (2024). What Is a Dividend Policy?, investopedia.com

- ^ Claire Boyte-White (2023). 4 Reasons a Company Might Suspend Its Dividend, Investopedia

- ^ See Working Capital Management Archived 2004-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, Studyfinance.com; Working Capital Management Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, treasury.govt.nz

- ^ a b Best-Practice Working Capital Management: Techniques for Optimizing Inventories, Receivables, and Payables Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Patrick Buchmann and Udo Jung

- ^ Security Analysis, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd

- ^ See The 20 Principles of Financial Management Archived 2012-07-31 at archive.today, Prof. Don M. Chance, Louisiana State University

- ^ William Lasher (2010). Practical Financial Management. South-Western College Pub; 6 ed. ISBN 1-4390-8050-X

- ^ a b Brian DeChesare. Corporate Finance Jobs

- ^ a b Shaun Beaney, Katerina Joannou and David Petrie What is Corporate Finance?, Corporate Finance Faculty, ICAEW, April 2005 (revised January 2011 and September 2020)

- ^ Nate Peach and Octavian Ionici (2024). Corporate Finance Analyst Jobs

- ^ a b John Hampton (2011). The AMA Handbook of Financial Risk Management. American Management Association. ISBN 978-0814417447

- ^ Risk Management and the Financial Manager. Ch. 20 in Julie Dahlquist, Rainford Knight, Alan S. Adams (2022). Principles of Finance. ISBN 9781951693541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See "III.A.1.7 Market Risk Management in Non-financial Firms", in Carol Alexander, Elizabeth Sheedy eds. "The Professional Risk Managers’ Handbook" 2015 Edition. PRMIA. ISBN 978-0976609704

- ^ David Shimko (2009). Dangers of Corporate Derivative Transactions

- ^ a b c d Aswath Damodaran. Corporate Governance: Defining the End Game

- ^ a b Capital Structure Policies : Debt, Equity and Options Theory, Ch 34. in Vernimmen et. al.

- ^ Damodaran, Aswath (2005). "The Promise and Peril of Real Options" (PDF). NYU Working Paper (S-DRP-05-02). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2001-06-13. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- ^ Capital Structure Policies : Capital Structure, Taxes and Organisation Theories, Ch 33. in Vernimmen et. al.

- ^ Jensen, Michael; Meckling, William (1976). "Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure". Journal of Financial Economics. 3 (4): 305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X.

- ^ Aswath Damodaran. Applications Of Option Pricing Theory To Equity Valuation Archived April 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

[edit]- Jonathan Berk; Peter DeMarzo (2013). Corporate Finance (3rd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0132992473.

- Peter Bossaerts; Bernt Arne Ødegaard (2006). Lectures on Corporate Finance (Second ed.). World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-256-899-1.

- Richard Brealey; Stewart Myers; Franklin Allen (2013). Principles of Corporate Finance. Mcgraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0078034763.

- CFA Institute (2022). Corporate Finance: Economic Foundations and Financial Modeling (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1119743767.

- Donald H. Chew, ed. (2000). The New Corporate Finance: Where Theory Meets Practice (3rd ed.). Non Basic Stock Line. ISBN 978-0071120432.

- Thomas E. Copeland; J. Fred Weston; Kuldeep Shastri (2004). Financial Theory and Corporate Policy (4th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0321127211.

- Julie Dahlquist, Rainford Knight, Alan S. Adams (2022). Principles of Finance. ISBN 9781951693541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Aswath Damodaran (1996). Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice. Wiley. ISBN 978-0471076803.

- Aswath Damodaran (2014). Applied Corporate Finance (4th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1118808931.

- João Amaro de Matos (2001). Theoretical Foundations of Corporate Finance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691087948.

- Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart, David Wessels (McKinsey & Company) (2020). Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1119610885

- Joseph Ogden; Frank C. Jen; Philip F. O'Connor (2002). Advanced Corporate Finance. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0130915689.

- C. Krishnamurti; S. R. Vishwanath (2010). Advanced Corporate Finance. MediaMatics. ISBN 978-8120336117.

- Pascal Quiry; Yann Le Fur; Antonio Salvi; Maurizio Dallochio; Pierre Vernimmen (2011). Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1119975588.

- Stephen Ross, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe (2012). Corporate Finance (10th ed.). Mcgraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0078034770.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Joel M. Stern, ed. (2003). The Revolution in Corporate Finance (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405107815.

- Jean Tirole (2006). The Theory of Corporate Finance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691125562.

- Ivo Welch (2017). Corporate Finance (4th ed.). ISBN 9780984004928.

Further reading

[edit]- Jensen, Michael C.; Smith. Clifford W. (29 September 2000). The Theory of Corporate Finance: A Historical Overview. SSRN 244161. In The Modern Theory of Corporate Finance, edited by Michael C. Jensen and Clifford H. Smith Jr., pp. 2–20. McGraw-Hill, 1990. ISBN 0070591091

- Graham, John R.; Harvey, Campbell R. (1999). "The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance: Evidence from the Field". AFA 2001 New Orleans; Duke University Working Paper. SSRN 220251.